Nigerian Education Conundrum: The Leadership Gap

A comprehensive assessment of the challenges of education in Nigeria has earlier grouped the challenges into 3 major gaps: The Access Gap, The Quality Gap, and The Outcome Gap. The access gap covers the challenges of education that limit people’s access to education, regardless of their age group. A detailed assessment of this was provided in a previous policy brief HERE. The Quality Gap addresses the challenges of education that add up to ensuring that the education access doesn’t live up to its expected ability to equip people for intellectual prowess and socioeconomic contributions. A previous policy brief dive fully into it HERE. The Outcome Gap explicates the challenges that low access to education and low quality of education instigates within the context of national development. A previous policy brief full describes it HERE. Upon closer scrutiny of the state of education in Nigeria, it becomes evident that there is a need to recognize another significant gap within the educational system. This crucial void is best described as the Leadership Gap.

Numerous scholars have endeavoured to define leadership, and a few of these definitions are

outlined below:

“Leadership is the ability to evaluate, and or forecast a long term plan or policy and influence the followers towards the achievement of the said strategy.” Adeoye (2009)

“Leadership is the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how to do it, and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives” (Yukl, 2010)

“Leadership is a set of behaviours used to help people align their collective direction, to execute strategic plans, and to continually renew an organization (McKinsey, 2022)

The leadership gap in Nigeria education comprises all challenges that impedes the ability to strategize and mobilise diverse resources essential in achieving an education system free from the challenges underpinning access, quality, and outcome gaps. This policy brief aims to provide an in-depth understanding of the issues surrounding leadership within the education sector while also offering recommendations to help bridge the existing gaps.

Understanding the Leadership Gap.

The leadership gap manifest 4 interrelated challenges:

- Lack of cohesive vision for current realities

The 1969 National Curriculum Conference formed the bedrock for the Nigerian’s philosophy of education. The conference, which happened at a time the nation was still reeling from the Civil War, became a launchpad for the indigenous education system in Nigeria. Some key outcomes of the conference includes the birth of the National Policy of Education and the 6-3-3-4 system which later evolved to the 9-3-4 system in 2008. Aside from its intentional decolonization efforts, an excellent feature of this conference was how it brought together Nigerian people from different walks of life to cohesively deliberate on a vision for Nigeria’s education. The conference in its aim to chart a vision for Nigerian education drew participants from all segments of the Nigerian society including academic institutions at all levels, local governments, various ministries, trade unions, publishing houses (Akanbi and Abiolu, 2019). Every part of the Nigerian socio-economic, political, and bipartisan institutions were represented including religious bodies, teachers associations, other professionals (medical, legal, engineering etc.), university teachers and administrators, ministry officials, youth clubs, businessmen, representatives of the then government of the 12 States of Nigeria and more (Dan Asabe, 2009). The government of the time thought it was necessary for the vision of education that was to emanate from the conference to be cohesively built by Nigerians so it could be owned by all. Adaralegbe (1972) succinctly described it as follows:

“It was not a conference for educationists alone; it was necessary to hear the views of the masses of the people who are not directly engaged in teaching or other educational activities, for they surely have a say in any decisions to be taken about the structure and content of Nigerian education.”

55 years later, Nigerian education system still largely runs on the 1969 vision. The National Policy on Education, although revised 5 times since 1969, still imbibes a view of education that doesn’t reflect much of the globalization trends of the 21st century world. Its most current version was published in 2013 i.e. 11 years ago, a testament to the fact that much of our current education vision is playing catch up with rapidly changing global dynamics.

Unlike the 1969 curriculum conference which made space for the input of the general Nigerian populace, the work of formulation of education policies in Nigeria in recent decades have been restricted mostly to policymakers with little involvement of the Nigerian public. Frequently, educators, who are intended to play a role in implementing education policies, often find themselves also excluded or overlooked during the formulation stages of these policies. The general populace, and sometimes teachers, are usually only informed of the policy after it has been decided by the policy makers.

Even concerning the dissemination of information, there are limited opportunities for direct public input before they are set on the trajectory toward implementation. A policy that has no public input is doomed to lack their buy-in also. It is no wonder there is little cohesiveness in the implementation of many would-have-been innovative education policies in Nigeria.

Current strategies to address this challenge involves work aimed at getting the public involved in charting a modern vision for Nigeria’s education in a cohesive, public-facing manner. They include works being championed by local organizations like The Policy Shapers, whose mission is to lead public-facing policy development processes by promoting policy ideation, dialogue, and advocacy that are led by young people in Nigeria. However, there remains the need for strong leadership that can rally the interest, buy-in, and commitment of the diversity of the Nigerian populace towards dreaming, strategizing, and executing a long-term vision of the kind of education necessary for the Nigerian to thrive in a modern world.

- The Intertwining of Education and Politics

Education, originally conceived as a public and apolitical good, has become entangled with the political landscape in Nigeria. The education system is designed in a way that makes the nation’s political situation central to its realities i.e., the outcome of education at a particular moment is closely intertwined with the ideologies, interests, and views of the political power of the day. Education is thus left at the mercies of becoming a power tool for the political class to enhance their interest and control the nation’s path. Different ruling classes gives different level of priority to education with evidence seen for example in a striking different educational budgetary allocation percentage across different tiers of government and different political affiliations. The implication is frequently evident in various scenarios, such as the discontinuation of innovative projects once they cease to align with the interests of the prevailing political class. This occurs, for instance, when initiated by an opposing political faction or when they no longer contribute significantly to consolidating the political class’s power.

Instances have arisen where the failure to implement or sustain policies occurs even within the tenure of the administration that initiated them. This can be attributed to various factors, including a lack of political will to persist or issues like corruption. An example is the School Feeding Programme that was inaugurated but later discontinued under the 2015-2023 presidential administration. At other times, implementation of policies are sometimes slowed down or completely side-stepped because of differing political will, affiliation and interests within the community of stakeholders responsible for implementing.

The influence of the nation’s political climate on the education system is further reflected in the substantial involvement of political interests in appointing administrators at various levels, ranging from ministries to universities. Frequently, considerations such as political affiliations, quota systems, and ethnicities take precedence over demonstrated educational and leadership capacities.

The towering influence of the political class on the education system is not without repercussions. An instance of such consequences, for example, is the erosion of trust in educational leaders. When stakeholders lack confidence in the capacity and competence of education leaders, it becomes significantly challenging for these leaders to galvanize collective efforts towards the shared objective of reforming the education sector.

- Education Leadership Capacity

Aside from teachers, another crucial human-capital contributor to the education landscape is the category of education administrators. They are responsible for the process of planning, administration, and management of the education sector. The structure of education leadership manifests itself in two primary levels of administrative scope: institutional-level and government-level.

The institutional-level encompasses the leadership structure within various tiers of education (primary, secondary, and university), featuring roles such as principals, proprietors, deans, vice-chancellors, and others. These individuals are responsible for guiding the leadership within their specific institutions. On the other hand, the government-level leadership structure is tasked with establishing and guiding the higher-level administration that governs the functioning of multiple educational institutions. This leadership is distributed across different tiers of government (local, state, and federal) and includes positions such as Ministers of Education, Commissioners of Education, Directors, and more.

Education leaders at these diverse levels and tiers are expected to have demonstrated capacity for education leadership. While many of these roles primarily involve administrative responsibilities, the intricate and rapidly evolving nature of the education sector demands that these leaders possess competence not only in administration but also in the nuances of education itself. The education sector differs significantly from other industries in its perspectives, scope, and practices. Consequently, education leaders need to possess not only general administrative skills applicable in any field but also sector-specific expertise essential for this distinctive domain. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Numerous educational leadership roles have been occupied by individuals who, while competent in other domains, lack demonstrated evidence of sector-specific capacity crucial for effective planning, administration, and management of the educational sector. Additionally, there is limited evidence of education leaders’ commitment to ongoing professional development, which is essential for consistent knowledge acquisition and capacity building. This lack of dedication to staying abreast of evolving global dynamics is particularly concerning, given the ongoing need for continuous evolution in how we both conceptualize and implement education.

- Education Financing

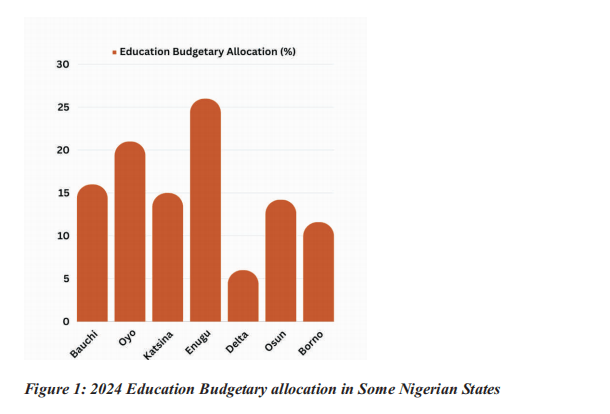

As previously highlighted, numerous decisions shaping the state of education in the country hinge on the inclinations of the political class. A critical example that warrants detailed exploration is the decision-making process regarding education financing. The decision for budgetary allocation for education at different levels of government lacks a specified national standard. Despite multilateral institutions like UNESCO recommending a 15-20% standard for budgetary allocation to education, as agreed upon by member states in 2015, this guideline is not consistently followed throughout the various tiers Nigerian government. Furthermore, the methodology employed in determining the budgetary allocation for education at various tiers of government remains unclear and is often influenced by the prevailing political power dynamics at that particular level.

It is not unusual to observe significant variations in budgetary allocations to education among different states and tiers of government. For instance, in 2024, Enugu state earmarked 26% of its budget for education, whereas Bauchi state and Ebonyi state allocated 16% and 6% of their budgets to education, respectively (See Figure 1). Conversely, at the Federal Government level, education received only 6.39% of the national budget.

The state of education financing within a specific tier of government thus heavily depends on the preferences of the political leader in charge. An illustrative example is the year 2019 when the budgetary allocation for education in Oyo state surged from 3% to 10% due to a change in the political leadership of the state administration. There remains the need for an education financing model that prioritizes the sector’s needs over the political inclinations of leaders.

Recommendations

- Education Vision Revitalization

The educational vision of Nigeria requires revitalization to align with the realities of the 21st century and to place the opinions and diversity of the Nigerian populace at the forefront. This necessitates an extensive, collaborative process between policymakers and the diverse Nigerian population to redefine a vision outlining the characteristics of an educated Nigerian, their abilities, and how they can contribute to the nation, the African continent, and the global community. A preliminary step could involve revising the existing version of the National Policy of Education through a model that actively involves the public.

- Nonpartisan Autonomy for Education Sector

The education sector must undergo a redesign that decentralizes political influence. The sector requires a nonpartisan sense of autonomy, where decisions are guided by clear, independent guidelines stemming from a renewed vision of education. This autonomy should also be maintained outside the full control of the political landscape.

- Continuous Capacity Building for Educational Leaders

Beyond establishing transparent processes for selecting education administrators based on demonstrated educational leadership capacities, it is imperative that administrators commit to ongoing professional development. Education leaders must embrace opportunities for training, workshops, and collaborative initiatives that foster not only administrative acumen but also a deep and current understanding of the dynamic landscape of education. By prioritizing continuous learning and growth, education administrators can effectively navigate the complexities of the sector, implement innovative strategies, and contribute to the sustained improvement of the education system.

- Clear guidelines for funding allocation

The education sector urgently requires enhanced financing, accompanied by clear and impartial guidelines for education financing that transcend individual political interests. This call for clarity is not novel, as certain aspects of education financing have already benefited from such transparency. For example, basic education is distinctly financed through concurrent contributions from the three tiers of government—federal, state, and local government authority, each with specified financing mandates and responsibilities for each tier. The federal government provides 50% and the state and local government as 30% and 20% respectively.

Extending such clarity to other areas of resource mobilization for education is essential. For instance, adopting a concise model to guide education budgetary allocation at all levels, regardless of the prevailing political landscape, would foster stability and consistency in funding. This model could establish predetermined percentages or criteria to allocate resources, mitigating the impact of political fluctuations on education financing.

References

Adaralegbe, A. (1969). A Philosophy of Nigeria Education. Ibadan: Heinemman

Adeoye, M (2009). A Leadership manager in Nigeria . Pearl publishing

Akanbi G.O and Abiolu O.A. (2018). Nigeria’s 1969 Curriculum Conference: A practical approach to educational emancipation. Cad. Hist. Educ. Vol.17 no.2. https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v17n2-2018-12

Dan-Asabe, A.U. (2009). National Policy on Education for Economic Reliance and Rehabilitation. Global Academic Group

Mckinsey (2022): What is leadership? Accessed online on 20 February 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-leadership

Yukl, G. (2010). Leadership in organizations (7th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.